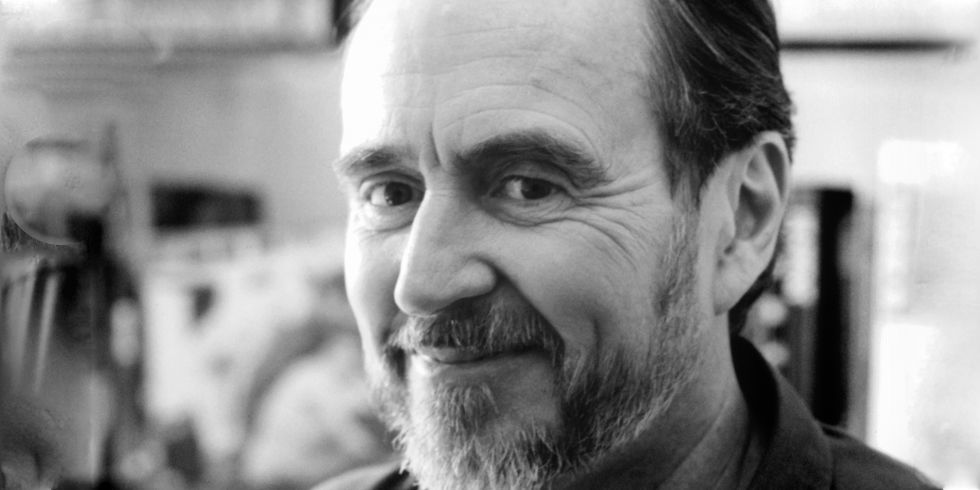

The term master gets thrown around a lot when talking about film-makers who’ve had a lengthy enough career. The pedigree of age becomes the only pedigree for entry into being considered a cinematic genius of some degree. Often times, when term master is applied to someone in cinema, the argument as to why boils down to “I just really, really, really like watching their movies”. Which is, ultimately what every discussion about film boils down to because experiencing and creating art are both completely subjective. There are some less arguable ways to vouch for someone’s claim to being a cinematic master – their contribution to the industry, their ability to consistently create, the evergreen nature and influence of what they commit to screen. Steven Spielberg is a master of cinema, David Cronenberg is a master of cinema. Wes Craven was a master of cinema.

Growing up the ’90s and noughties (indulge me for a second here), I was part of the last generation who knew the feeling of browsing a video store for something to rent on the weekends. The smell of the cheap cleaning solution as you walked in the door, the sight of the shelves and shelves of movies across all genres, the selection seeming limitless. I discovered a great many films through simply picking up a cool looking covers from the horror section of my local video emporium, so many in fact that by the time it was closing, I could name that entire section off by memory (I literally hung around the horror shelves even when we were only renting a new release instead of a couple of oldies, it was an early comfort zone). Of the tapes I managed to convince my father to rent for me, a few stand out as being particularly influential, but none moreso than Scream. I wasn’t allowed watch Scream when I was very young, but I eventually managed to talk my dad into letting me see it, mostly because by that stage Scream 3 had happened and the shocking press had died down. A couple of months later I saw A Nightmare On Elm Street for the first time.

Anecdotally, most of the other horror and film fans I know discovered Craven through similar means, by beginning to experiment with the odd, misshapen looking covers at the video store. It’s an experience I’m willing to wager is common to anywhere that had a video store with a semi-regularly updated selection. Craven‘s body of work is one of the great gatekeepers of horror and it’s difficult to fathom anyone somehow avoiding having seen at least something he’s done, even if they’re not strictly fans of scary films. In fact, I’d even go so far as to say he may be the most important horror film-maker when it came to creating movies that would become entry points into the genre. Looking through his filmography is like a laundry list of different works that achieve more in one film than most creators could ever hope for in their career. It wasn’t until my teen years when I had access to the money to start cultivating a collection of my favorites that I realised that so much of what made me care about horror, and film in general had come from him.

That was the genius of how he created. Somehow, Craven had a way of tapping into both where film and pop culture were and where they were going, and that intersection is where he lay claim, time and time and time again. Like many of the independent film boom of the ’60s and ’70s, his first production was an outlandish, rebellious, coarsely made piece with bold ideas and bolder presentation. The Last House On The Left, a proud member of the class of video nasties that reached cult status through stark infamy, was already enough to cement him in film history. However, unlike most of his graduating class of nasty, Craven wasn’t to be contained nor defined. His follow-up was The Hills Have Eyes, a slasher pseudo-apocalyptic condemnation of the othering attitudes and nuclear mumblings of the time.

Though Freddy Kreuger’s dominance of the world of nightmares with A Nightmare On Elm Street and the meta-reinvention of Scream are what gave him his pop culture saturation, Craven was already a seasoned pro before mainstream attention ever truly beckoned. He even gave the world an early, obscure comic book movie in Swamp Thing, cementing his doing-it-before-it-was-cool cred. The simple truth is that Craven was a different breed to his peers in horror. When his definition was outmoded, he would work to redefine once again, taking the genre as a whole forward. Scream, the trilogy that would be his final major feature, is both a rebirth and epitaph, a loving giggle at what’s come before with a slightly cynical nod that new blood is needed and that perhaps what the world needs isn’t another sequel from another old school film-maker. Craven accepted his old age with grace, continuing to make the films he wanted as he wanted to make. Among his final movies is a contribution to French anthology Paris, Je T’Aime, in which he shared reel-time with the likes of Alfonzo Cuaron (Gravity) and the Coen brothers – a poetic portrait in film of the city of Paris.

The world of horror owns a debt to Mr. Craven that is immeasurable. Though no doubt he will be succeeded, because his influence was that dam great, cinema feels ever more cavernous for his absence. A career spent scaring, comforting and scaring again; what a pleasure it is to have known such sweet terror.