Christopher Nolan’s latest blockbuster is one of the most hotly anticipated films of the year, and deservedly so. Not only does it mark the illustrious film-makers return to both directing and writing, but it also happens to be his first original screen-writing since the Dark Knight trilogy ended in 2012. Moving on from the streets of comic book panels and the current superhero trend that he was instrumental in kickstarting, the Inception director has decided to set his sights higher and further than he ever has before, moving from the world of dreams into a dream of worlds. Taking a typically strong cast with him and armed with the usual mystique and promise, Nolan has created a film that is every bit the visual feast we’ve come to expect, but isn’t  quite as air-tight in its story-telling as previous efforts.

quite as air-tight in its story-telling as previous efforts.

In his first outing since becoming an Academy certified Best Actor, Matthew McConnaughey heads up Interstellar as Cooper, a widowed astronaut struggling with two children on a desolate Earth. Cooper’s relationship with these children is mixed at best, with his father-daughter connection with youngest Murph, played by Mackenzie Foy, being the center-point. Much of the emotional nuance through-out the film is hinged on this, and the strength and traversal of the love of parent and child through time and space. Along with his children, Cooper is assisted at home by Father-In-Law Donald, played by John Lithgow, who helps out while Cooper looks after their expansive corn farm. A farm, we soon learn, is dying slowly and there’s nothing we can do about it. Our home planet has hit a famine that we can’t seem to solve, and our supplies are running low. Our only hope? A mission to find new worlds and new civilizations, and to boldly go where no man has gone before… Wait, sorry, wrong movie! But most of that still stands. Cooper, along with Anne Hathaway’s Amelia Brand, Romilly (David Gyasi, Cloud Atlas) and Doyle (Wes Bentley), are tasked with flying off into the stars above in order to find some previously scoped out planets (with the help of Michael Caine’s Professor Brand) and see if they are hospitable enough for the human race to move there in a hurry.

Much of what makes Interstellar so appealing is the sense of mystery that has become commonplace surrounding Christopher Nolan’s personal ventures. Like its thematic sibling Inception, the intrigue surrounding Interstellar is as much about the audience seeing the film as it is about the adventure the characters in the film are undertaking. There’s a connection between the two making a journey of discovery together that has played a strong part through-out Nolan’s filmography, going back to his earlier more personable works with Memento and Insomnia. While there’s a stark difference between those more down-to-Earth stories and this literally out of this world tale, the lengths the Nolan goes to to establish a conducive co-habitation between both the actors and audience in the reactions is evidenced in his reliance on practical effects.

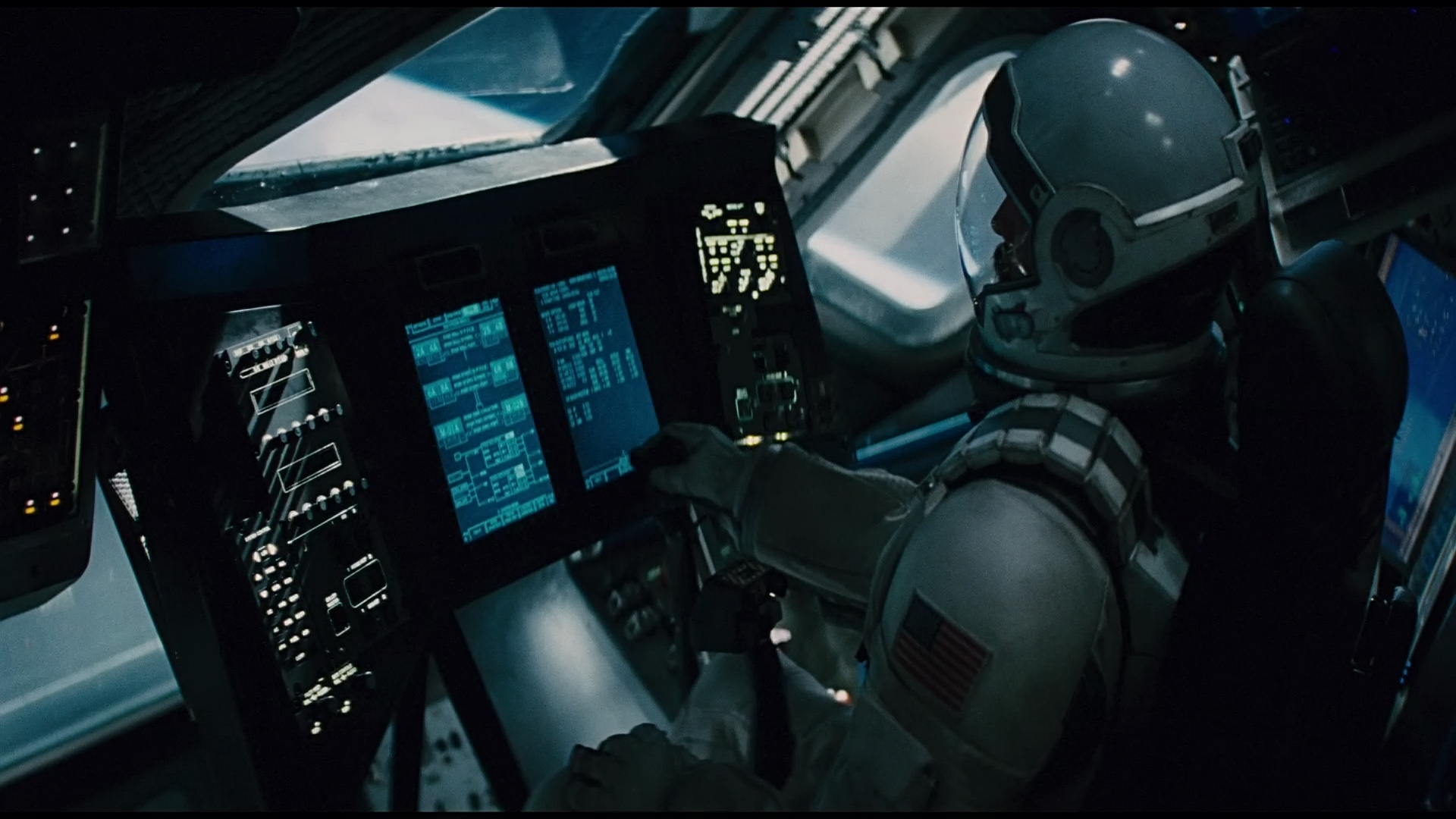

As much as is humanly possible with a production such as this, practical, tangible sets are utilized, down to the ship’s windows in shot while the crew converse/fly having been plastered with the star patterns that are in view. The gritty, almost-wasteland that is currently Earth suffers from regular, literal dust-storms as dust is blown through the streets in scenes, giving a very real impression of how desperate the situation is at home. Combining these environmental flourishes with on-location shots creates a tangible environment that begs to be explored and admired, rather than just passing set-pieces to be played in. Even down to Hans Zimmer’s soundtrack, which uses a lot of ambient organ, amongst other more earthly sounds, to give waves of warmth to these environments. The extent of these designs is staggering, with every interaction with a console on the ship’s bridge giving a sense of realness often lost in today’s often CGI-soaked movie environment, harkening back to a bygone era of science fiction championed by films such as 2001: A Space Odyssey and Silent running.

As much as is humanly possible with a production such as this, practical, tangible sets are utilized, down to the ship’s windows in shot while the crew converse/fly having been plastered with the star patterns that are in view. The gritty, almost-wasteland that is currently Earth suffers from regular, literal dust-storms as dust is blown through the streets in scenes, giving a very real impression of how desperate the situation is at home. Combining these environmental flourishes with on-location shots creates a tangible environment that begs to be explored and admired, rather than just passing set-pieces to be played in. Even down to Hans Zimmer’s soundtrack, which uses a lot of ambient organ, amongst other more earthly sounds, to give waves of warmth to these environments. The extent of these designs is staggering, with every interaction with a console on the ship’s bridge giving a sense of realness often lost in today’s often CGI-soaked movie environment, harkening back to a bygone era of science fiction championed by films such as 2001: A Space Odyssey and Silent running.

But with this being a sci-fi blockbuster, there’s healthy morsels of computer-generated special effects at play, too. They’re just used sparingly, and to great effect. Huge tidal waves are contrasted with planetary goliaths to create in the most literal term an awesome spectacle. In fact, I’d go so far as to say that Interstellar’s special effects are used only as a compliment to the more real, physical story being told, rather than the opposite, which tends to be closer to the bone for many of its alumni today.

It would be easy to compare Interstellar to 2001: A Space Odyssey in its grand story-telling and abstract metaphor on existence, but I find that the solipsist themes and leanings towards existentialism have quite a bit in common with space horror Event Horizon. Paul W. S. Anderson’s third directorial feature has little in common in execution with Interstellar, with its gore-filled narrative and emphasis on hallucinogenic episodes to truly creep out the viewer, but the attempts to view and critique one’s place in the universe remains starkly similar. Casting a reflective view on who and what we are while also telling a story of how we can overcome and challenge both is ambitious to say the least, and Event Horizon‘s outcome is one that definitively says ‘No, that’s a bad idea’ while Interstellar takes a more ambiguous route, if a touch lax in its outcome. Thankfully, Cooper and co. get to keep their eye-balls in their sockets, too, which is always nice.

Even with its somewhat narrative failings, Interstellar is still a triumph in cinema. Every member of the cast turns in a career highlight performance, with Anne Hathaway and Matthew McConnaughey undoubtedly leading the pack. Nolan proves once again what a visual master he is, and if anything this is a reassurance that even with a slightly off screenplay, he can still bring an exciting, worthwhile film to the screen.

Slightly overlong sci-fi epic with awesome visuals and a compelling narrative. 8/10