No Man Is An Island

Well, except when he’s having a bath.

An adult male may not be a landmass surrounded by water, but we all begin life as tiny human babies blank even of language, and we spend a lifetime building our world from the ground up. Childhood is a never-ending quest for new data; making connections; a whirl of theories projected and rejected as ever more complexity is revealed. Reality is just too big to describe, so we look to stories about childhood against which we may measure the value of our own. We receive our wisdom from the people we are taught to trust. If we’re unlucky, we learn not to ask questions. If we’re lucky, they’re only half wrong.

The world is small when we are young, and as it grows we stretch to fit, if given the chance. Each inner world is in constant negotiation with the worlds of others, finding in them echoes, allies, opposites, villains, heroes. We give our loved ones real estate in our worlds, and vice-versa. When they are made to feel invisible, we see them. Give us the most wretched of external environments, the most unfair of societal arrangements, the most painful of inner experiences, and what do we do? We sing, or we dance, or we laugh.

Always, we tell stories.

So it’s storytime again, only now you, dear reader, get to be the hero. Answer as fully as you wish.

- What are the limitations of your world? Can you acquire power to overcome your limitations? Can you achieve it through work alone, or will you need luck? What will that power cost you?

- What comes easily to you? Is it possible for a person to turn that into a source of power? Is it possible for you? Do you have access to the necessary resources to turn your aptitude into skill?

- What’s in your rucksack? What are the assets you were born with or given by others? Are they rare or common?

- What is your honour code? Was it inherited or did you write it yourself? What do you believe is the worst thing one person can do to another? Was that ever done to you?

- What’s your Chaos factor (potentially debilitating recurring circumstance you cannot control)? Does someone else choose to impose it on you? What gives them that power? Is there help available to you?

- In all the centuries of known fictional stories, how many were about people like you? How many were written by people like you? How many were written for people like you? Whose stories are told? What do they have in common?

- Are there words for your troubles? (Imagine being dyslexic before they knew it was a thing, trying to explain that you just do not see what they see – what else do we not have words for yet?) When you speak about your inner experiences, do people listen? Do they believe you?

Congratulations. You have just articulated your own 1) personal obstacles, 2) potential power source, 3) individual resilience, 4) moral code, 5) archnemesis, 6) historical visibility, 7) access to authority and awareness of the limitations of language to describe reality outside of social norms. Quite the busy paragraph, no?

If, hypothetically, there was another person born right where and when you were born, with the same rucksack and an experience of childhood that eerily mirrored yours, that person still would not have answered the above questions in the exact same way you just did. With the immense variation possible in even those four starting factors, it grows harder to take seriously any kind of generalising about people.

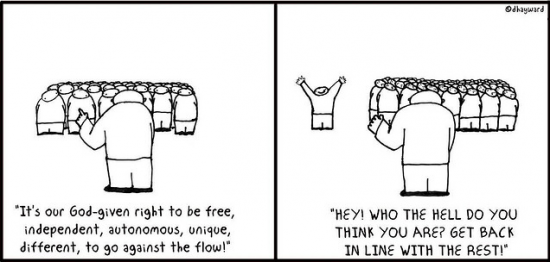

We are all individuals. We are all different. Even you.

At this stage, take it as read that no matter how well someone else thinks they know us, we are always going to know ourselves better. We are the experts on our own experience, because we are the only ones who’ve seen all the episodes. Actually, we wrote, directed and starred in them to boot. But again, this cuts both ways, as we are also unable to identify our own privileges until we are given a context in which they are a variable and not a constant. Privileges are the aspects of your identity that do not restrict you because they are already the default in your society, so you just don’t have to think about them very often.

At the end of the previous article was a question, but the answer was not the point. That some of us did not notice the answer staring us in the face until we were asked the question, that is the point. People don’t remark on the unremarkable, yet what is remarkable depends on the individual. If you do not work to identify your privileges, you will fail to see how in a society that suits you just fine, other people may fit as comfortably as an Ent in a hobbit hole. Likewise, taking an individual’s experience and extrapolating about entire groups of people will fail to describe their actual reality in any but the most reductive, simplistic terms.

So, if generalising about people is in general useless, why continue to do it? Well, it’s just like with any other self-respecting placebo; if you buy it, it works. Useful ideas tend to survive across generations, and believing that people can be categorised according to false binaries is a useful idea.

For example, it is useful for someone, somewhere, to have people believe as fact that your biological sex also dictates your gender, values, personality, libido and career path rather than just describing which set of genitalia you appeared to possess at birth.

It is useful for someone, somewhere, to have people believe as fact that gender is a fixed concept rooted in magical essences rather than the performance of social roles according to the prevailing norms of the time.

It is useful for someone, somewhere, to have people believe as fact that human variation can be arbitrarily divided into binary opposites and the failure to shrink your experience to fit that division is a failure of the individual and not of the system attempting to describe them.

It is useful for someone, somewhere, to have people believe as fact that humans come in flavours akin to the ice-cream selection in a small rural shop – such as off-brand strawberry or dubious banana – when really, like wine or tea or cheese, humanity possesses a flavour range of near-infinite subtleties which will further vary in experience according to vintage, serving temperature, and accompanying nibbles.

It is useful for someone, somewhere, to have people work really hard to make sure that the next generation are also raised believing this fiction to be fact, and that any variation in internal truth the individual may possess is something to be discouraged, banned or beaten out of them.

That someone, somewhere, is not a shadowy figure sitting in a hollowed out volcano stroking a cat and monologuing over the success of their plan. It’s me. It’s you. It’s everyone. For different reasons and to varying degrees, yes, but there are fictional truths we all benefit from.

The person constrained by fictional truths? Also me, also you, also everyone; because fictional truths do not accurately describe real people.

Even the most straightforward, predictable, consistent human being on the face of the planet is far more complex than any fictional character ever written, for one single reason: we exist across time, and they do not.

We journey, and they do not. We change. They do not. Characters are the product of a moment; we have a million moments. Time passes. We live once upon a time, and then again, and again. We edit ourselves; we rewrite our origin story; we direct our sequels. We break the limits of our happily ever afters, and start over.

We exist. Simples.